The next six months will be a defining period for Nepal's hydropower sector as six projects, each exceeding 100 MW, reach financial closure. This milestone is particularly significant because all these projects are being developed by Nepali independent power producers (IPPs), marking a major breakthrough for the country's private sector in the energy industry.

This scaling up of Nepali IPPs represents a transformative shift. Having started in the early 2000s with projects as small as 1 MW, these independent producers have steadily built their capacity and expertise, reshaping Nepal’s hydropower landscape.

According to the Independent Power Producers Association, Nepal (IPPAN), five private-sector-led hydropower projects exceeding 100 MW have already completed financial closure. Additionally, 11 more are in the final stages of securing financing, signaling strong momentum in private-sector-driven hydropower development.

Among the projects nearing financial closure is the 341 MW Budhi Gandaki Hydropower Project, the largest private-sector hydropower venture to date. The project gained attention when Sahas Urja acquired it from Times Energy in January 2024 for Rs 2 billion. Sahas Urja Chairperson Him Pathak exemplifies the sector's evolution. Pathak started with the 5 MW Upper Hugdi Khola project, and later developed the 86 MW Solu Khola which is the largest private-sector project in operation at present. Now, with Budhi Gandaki, he is taking an even bigger leap.

Similarly, another major development took place on June 6, 2024, when Tamor Energy Pvt Ltd secured investment for the 285 MW Upper Tamor Semi-Reservoir Hydropower Project. A consortium of eight banks and financial institutions, led by Everest Bank, has signed a loan agreement of Rs 38.60 billion with Tamor Energy.

This project marks a major milestone for Tamor Energy Chairperson Pushpa Jyoti Dhungana. Dhungana, who entered the hydropower sector in 2008 with the development of the 1 MW Patikhola Hydropower Project, has experienced firsthand the challenges of mobilizing resources and securing technical expertise. The Upper Tamor project, fully funded by local investors and designed by Nepali firm Sanima Hydro and Engineering, is a testament to the domestic sector’s growth.

This surge in private-sector involvement builds on a foundation laid decades ago. The 60 MW Khimti Hydropower Project, which began commercial operations on July 11, 2000, was a watershed moment for Nepal’s hydropower industry. It was the first privately developed project since Nepal’s hydropower generation began in 1911 with the 500 KW Pharping Hydropower Project. Khimti's success paved the way for further private investment, leading to projects like Bhotekoshi Hydropower—both of which became Nepal’s first private-sector ventures with foreign investment.

IPPs Scaling Up Capacity

The private sector has been instrumental in Nepal’s hydropower development. While the country’s hydropower history spans 114 years, significant progress has only been made with private sector involvement. Since 2000, when the first privately funded project began generating electricity, independent power producers (IPPs) have added over 2,000 MW—far surpassing the government’s 90-year production of 600 MW.

Nepal's total hydroelectricity production currently stands at approximately 2,800 MW, with the private sector contributing around 2,100 MW. Hydroelectric projects with a combined capacity of 3,200 MW are under construction, while projects totaling 3,500 MW are in the financial closure stage. Meanwhile, projects with a total capacity of 12,000 MW are awaiting power purchase agreements (PPA) with the government. Of the nine projects exceeding 100 MW that have successfully completed financial closure, five are private sector-led, and all 11 projects currently in the financial closure process are being developed by private investors.

Several large-scale hydropower projects have successfully completed financial closure. Among them is the Upper Tamor Hydropower Project in Taplejung with an installed capacity of 255.281 MW developed by Sanima Energy Pvt Ltd. This project reflects the private sector’s growing expertise in handling mega ventures. “Over the past two decades, the private sector has gained valuable experience, and it is now capable of undertaking large-scale projects,” said Pushpa Jyoti Dhungana, Chairperson of Upper Tamor Energy.

In Dolakha, the Lapche Khola Hydropower Project, developed by Nasa Hydropower Pvt Ltd, boasts a capacity of 160 MW. Similarly, the Manang Marsyangdi Hydropower Project, led by Manang Marsyangdi Hydropower Company Pvt Ltd, will contribute 135 MW from the mountainous region of Manang. The Rasuwa Bhotekoshi Hydropower Project (120 MW) in Raswua, promoted by Langtang Bhotekoshi Hydropower Company Pvt Ltd, has secured financial closure, while Super Trishuli, a 100 MW project on Trishuli River, is being developed by Blue Energy Pvt Ltd.

“The rapid expansion of private sector-led hydropower projects underscores its vital role in Nepal’s energy sector. With ongoing developments and future plans, the private sector remains a driving force in achieving the nation's energy independence and economic growth,” said Ganesh Karki, President of IPPAN.

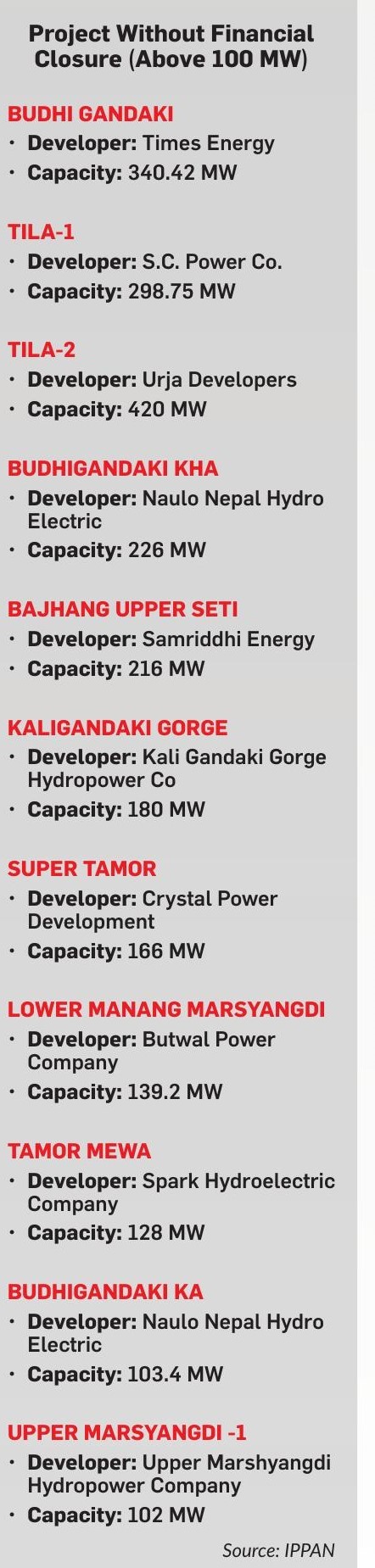

While several projects have secured financial closure, many others are still in the process. Among the largest projects awaiting financial closure is the Budhi Gandaki Hydropower Project which is being developed by Times Energy Pvt Ltd. With a planned capacity of 340.42 MW, this project in Gorkha has the potential to be one of Nepal’s most impactful energy ventures.

In Kalikot, Tila-1 (298.750 MW) project is promoted by S C Power Co. Tila-2 (296.740 MW) is being built by Urja Developers. These projects will play a crucial role in strengthening power availability in the mid-western region.

Another key project in Gorkha, Budhigandaki Kha (226 MW), is being developed by Naulo Nepal Hydro Electric Pvt Ltd. The company is also building Budhigandaki Ka (103.4 MW) in Gorkha.

Similarly, in Bajhang, Bajhang Upper Seti (216 MW) being built by Samriddhi Energy Ltd will play a crucial role in addressing energy needs in the far-western region.

In Myagdi, the Kaligandaki Gorge Hydropower Project, led by Kali Gandaki Gorge Hydropower Co Pvt Ltd, will generate 180 MW. Meanwhile, in Taplejung, Super Tamor, a 166 MW project by Crystal Power Development Pvt Ltd, would play a vital role in strengthening the eastern energy grid.

Further supporting Nepal’s energy infrastructure is the Lower Manang Marsyangdi Hydropower Project, a 139.2 MW initiative by Butwal Power Company Ltd, in Manang. It is expected to enhance grid stability and energy distribution in central Nepal. Another key project in Taplejung, Tamor Mewa, developed by Spark Hydroelectric Company Ltd, will contribute 128 MW to the region’s energy supply.

In Lamjung, the Upper Marsyangdi-1 Hydropower Project, developed by Upper Marshyangdi Hydropower Company Pvt. Ltd., will add 102 MW to the national power grid.

As these projects move toward financial closure, they represent a significant step in Nepal’s path toward energy self-sufficiency, while showcasing the growing expertise of Nepali IPPs in executing large-scale projects.

One company leading this transformation is Urja Developers. Established in 2016, the company started with two small projects and is now aiming to generate 1,000 MW by 2030. Bhanu Pokharel, Group Managing Director of Urja Developers, said that the company currently has four hydropower projects, ranging from 9.3 MW to 78.5 MW, under construction. It is now planning to build the 420 MW Tila-2 Project.

Too many constraints

The hydropower sector faces significant infrastructure challenges that hinder project development, financial closures and operational efficiency. These constraints not only increase costs but also threaten the long-term sustainability of the industry.

One of the biggest challenges is the high cost of infrastructure development, particularly for road construction and transmission lines. For instance, in the Pathi Khola 1 MW Project, the first project developed by Pushpa Jyoti Dhungana, costs escalated due to the need to build roads and transmission lines to connect to the national grid. The lack of infrastructure in remote areas extends project timelines and inflates budget, making hydropower projects expensive.

“At that time, cement prices were also steep, further driving up overall project costs. Unfortunately, there has been no policy intervention to support small-scale hydropower developers,” said Dhungana. “Without a clear path to reasonable returns, investors will hesitate to fund new projects.”

Policy inconsistency and bureaucratic delays pose another significant hurdle. The 15 MW Hewa Khola Project, for example, faced long setbacks due to government inefficiencies. In one case, critical project materials remained stuck in customs for months despite promised tax exemptions. This led to cost overruns and extended timelines. “The government assured us of a tax exemption on spare parts worth Rs 100 million, yet they were held up at customs for eight months. This delay added Rs 1 billion to our costs and significantly slowed progress. Such policy inconsistencies discourage investors from pursuing new hydropower projects,” Dhungana said.

The government has introduced tax exemptions on customs duties, value-added tax (VAT) and import duties for construction materials, tools and spare parts used in hydropower projects. However, developers argue that these exemptions exist only on paper, as bureaucratic hurdles continue to delay imports. While equipment is officially subject to only a one percent customs charge and full VAT exemption, procedural obstacles make the process anything but seamless.

IPPAN has repeatedly urged the government to grant a 15-year tax exemption for energy projects, including hydropower, until Nepal reaches 28,500 MW of electricity generation. Their demands include capping customs duty on imported machinery and equipment at 1%, eliminating taxes on electricity sales and incorporating electricity into VAT-taxable items to ensure financial sustainability for developers.

Another major challenge is Nepal’s inadequate transmission network. While electricity production is increasing, existing transmission infrastructure is incapable of handling the growing load. This is particularly problematic for large-scale hydropower projects that rely on robust grid systems to efficiently transfer electricity. Without sufficient transmission capacity, completed projects risk facing delays in power supply integration.

IPPAN President Karki stressed the urgency of upgrading the transmission network to support private-sector-led hydropower projects. “Since most hydropower projects in Nepal are run-of-the-river, they generate peak electricity during the west season. But without proper transmission infrastructure, projects cannot operate at full capacity, even in peak months,” he said. “Transmission line construction delays are causing significant financial losses for private developers. Allowing private companies to build transmission lines could help reduce energy wastage and ensure efficient electricity delivery. Private sector involvement would bring necessary investment and innovation to accelerate Nepal’s transmission network expansion.”

Hydropower developers also struggle with rising costs of construction materials. The cartel of cement and iron bar manufacturers has caused prices to soar, further driving up project costs.

“The government has done nothing to control price manipulation by cement and iron manufacturers. Yet, when project costs rise, we are the ones questioned about overruns,” said Karki. “We are forced to sell power at government-mandated rates while dealing with inflated material costs that are crippling the industry. Cartel-driven price hikes are making hydropower projects financially unsustainable.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge is Nepal’s complex and time-consuming approval process. Developers must secure multiple licenses for electricity generation, transmission and distribution, each requiring separate approvals and lengthy bureaucratic procedures. Additionally, projects must undergo mandatory environmental assessments, such as Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) or Initial Environmental Examinations (IEE), depending on their scale. These assessments require clearance from the Ministry of Forests and Environment, with large-scale projects (exceeding 25 MW) often facing an even more intricate approval process, sometimes requiring cabinet-level approval.

“This is how the government welcomes the private sector to produce 28,000 MW of electricity,” said Sailendra Guragain, former president of IPPAN. “Unless the government adopts a single-window policy for approvals, developers will continue to suffer. Right now, we need nearly two dozen approvals, forcing us to spend months running between government offices just to move projects forward.”

The issue of funding

While the capacity of Nepali banks and financial institutions to fund hydropower projects has increased in recent years, IPPs argue that securing financing remains one of the most pressing challenges. Over the past few years, Nepal's banks and financial institutions (BFIs) have provided loans through consortium financing, with a majority of IPP-led projects relying on domestic funding.

One of the primary obstacles in financing is the limited access to project-based funding. Although Nepal’s banking sector has strengthened its capital base and liquidity, lending models still rely heavily on collateral-based loans rather than more flexible project-based financing. This creates a significant hurdle for hydropower developers, who require funding based on the expected revenue and cash flow of a project rather than physical assets. The lack of long-term financing options with favorable terms makes it difficult to secure capital for large-scale infrastructure projects, particularly those requiring multi-million-dollar investments.

According to the government’s energy roadmap, Nepal needs approximately $46.5 billion to achieve 28,500 MW of electricity generation within the next 10 years. However, given that local banks and financial institutions lack the capacity to provide such substantial funding, hydro developers stress the need to attract private investment and foreign direct investment (FDI) to bridge this financial gap.

"Such amounts are not currently available within Nepal's banking sector. Therefore, we must create investment opportunities for foreign companies," said a hydropower developer.

According to Guragain, many projects are struggling to achieve financial closure due to collateral-based lending models of banks. "Nepal Rastra Bank mandates that a certain percentage of bank investments be allocated to agriculture, tourism and hydropower. However, this policy needs revision. There should be a mandatory requirement for banks to invest at least 20% of their portfolio in hydropower projects. This would ensure adequate capital for the sector," said Guragain.

Another major barrier is the cap on individual bank lending. Currently, a single bank can provide only 25% of its total capital as a loan to a single hydro poject, which significantly restricts its ability to fund large-scale hydropower projects. Additionally, high equity requirements for hydropower projects make it difficult for developers to raise sufficient capital. Large-scale projects often require funding from multiple banks, making it difficult for individual developers to meet the equity portion of their investment.

"Since banks have lending caps, individual institutions can only finance a limited portion of a project. As a result, developers struggle to raise enough funds from domestic sources alone," Guragain explained.

A significant number of hydropower projects are stuck in the financial closure phase, despite securing Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs). Over 4,000 MW of signed projects are still awaiting financing, with developers struggling to obtain equity funding or loans, according to IPPAN.

"If Nepal is to generate 28,000 MW of electricity within the next decade, the government must facilitate companies to achieve financial closures instead of leaving it entirely to the private sector," Guragain added.

In addition to financing constraints, Nepal also faces challenges in executing large-scale projects, particularly in engineering and construction. According to Pokharel, Nepal has experienced liquidity surpluses and crises, creating uncertainty in debt financing. "To ensure financial stability, Nepal needs a balanced mix of debt financing, equity and foreign investment. In partnership with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), we introduced mezzanine financing in Nepal, structured as an NPR-denominated instrument worth $21 million. However, Nepal Rastra Bank, which appears hesitant due to its unfamiliarity with the concept, has delayed its approval," Pokharel explained.

Mezzanine financing, which blends debt and equity financing, could provide a much-needed alternative to traditional loans. However, the slow approval process has prevented its implementation.

Market Uncertainties and Export Challenges

Nepal has set ambitious hydropower targets, aiming to generate 28,500 MW of electricity in the coming years. This expansion is largely driven by private sector involvement which has already contributed 2,100 MW, with an additional 4,500 MW under construction and 3,000 MW at the financial closure stage. These figures highlight the private sector’s capacity to execute large-scale projects and significantly boost Nepal’s energy production.

Despite this positive momentum, there are concerns about the market’s ability to absorb the projected energy output. While Nepal has immense hydropower potential, domestic demand is still too low to justify such large-scale expansion. The country continues to import electricity from India during the dry season, when domestic production declines.

Although Nepal has negotiated power export agreements with India and Bangladesh, ensuring these deals materialize remains a challenge. India’s demand, for example, is not guaranteed. While long-term agreements allow Nepal to export up to 464 MW, there is uncertainty about whether these agreements will scale up—especially if India meets its own energy needs or turns to alternative sources.

Political instability and geopolitical tensions further threaten Nepal’s hydropower sector, according to Sanjeev Neupane, Managing Director of Api Power Company. "As we move toward mega projects, there is a growing concern that political instability and geopolitical challenges could disrupt Nepal’s ability to export surplus electricity to India or other countries. These uncertainties threaten long-term hydropower investments," he warned.

A stark example of geopolitical risks emerged last year when India refused to buy electricity from Nepali hydropower projects that were built with direct Chinese investment. This highlights the vulnerability of Nepal’s export market to political and diplomatic tensions.

Furthermore, fluctuations in energy prices in India and Bangladesh could reduce demand, making it difficult for Nepal to maintain stable revenue from electricity exports. While the private sector is eager to tap into international markets, doubts remain about whether these agreements will provide consistent long-term returns.

Another critical challenge is Nepal’s inadequate transmission infrastructure. While power generation capacity is expanding rapidly, the transmission network has not kept pace. This creates a major risk of energy spillage, leading to financial losses for developers. Without urgent investments in transmission and distribution networks, even the most ambitious hydropower targets may become unrealistic. Weak infrastructure could prevent Nepal from fully utilizing its hydropower potential, undermining the economic viability of large-scale energy projects.

Dhungana, however, believes that Nepal need not worry about finding a market for electricity. "There is a concern that if India does not buy Nepal’s surplus electricity, the hydropower sector will suffer. However, Nepal still imports 700 MW of electricity from India, costing Rs 22–25 billion annually. To become energy independent, Nepal must ensure a reliable domestic supply even during the dry season. This requires maintaining a 20% spare energy reserve to account for disruptions caused by floods or seasonal variations," he explained.

Dhungana argues that stopping electricity imports from India would allow NEA to offset revenue losses through fair tariffs. "Currently, about 33% of annual hydropower revenue is lost during the four-month wet season due to energy spillage. Even if some projects shut down during peak generation months, financial sustainability can still be maintained," he added.

A more pressing concern is Nepal’s slow industrial growth, which limits domestic electricity consumption. Without a substantial increase in industrial demand, surplus electricity risks being wasted or underutilized. "If India reduces electricity imports, Nepal should use surplus energy as a raw material for value-added industries. For example, high-grade iron production requires substantial electricity consumption. Silicon production, using sand and hydropower, is another potential industry. Data centers also need stable electricity, presenting another sector for investment," he suggested.

Guragain agreed with Dhungana. "In areas like Rasuwa, we can provide electricity at Rs 5 per unit—without involving NEA as an intermediary. Currently, industries pay Rs 11 per unit to NEA. If the government creates industrial zones near hydropower plants, both industries and power producers would benefit," he added.

A direct supply model would reduce costs for industries, boost manufacturing growth and create a sustainable domestic electricity market.

Nepal is not even consuming 2,000 MW today. This raises concerns about the viability of future hydropower expansion. Transmission line expansion remains another bottleneck. Only 4% of Nepal’s total energy consumption comes from electricity, while 70% still relies on biomass. Nepal’s per capita electricity consumption stands at just 400 kWh per year—one of the lowest in the region.

"Even if we increased per capita consumption to 1,500 kWh, there would still be room for growth. Nepal needs to raise electricity’s share in total energy consumption from 4% to at least 30-40%," said Pokharel. “Nepal’s power generation is dependent on NEA. But what if NEA fails to sell surplus power in the future? What if India stops purchasing due to geopolitical issues? What if NEA’s financial health deteriorates? These are major risks that must be addressed," he said.

Unbundling NEA

Power producers say one of the major challenges in the hydropower sector is the existing structure of the state-owned utility NEA. The NEA is responsible for policy-making, electricity trading, transmission and power generation. These too many roles are resulting in operational inefficiencies, hindering private sector involvement. Many industry experts believe that unbundling the NEA could improve efficiency, foster competition and create a more dynamic, market-driven sector.

Unbundling would involve separating NEA’s different functions into distinct independent entities, each responsible for specific tasks such as generation, transmission, distribution, and policy-making. This model has been successfully implemented in many other countries, leading to greater transparency, efficiency, and private sector participation.

Neupane of Api Power Company believes NEA should be unbundled to improve the hydropower market. "In no other country does a single institution handle duties like policy-making, electricity trading, transmission line development and project implementation. Currently, the private sector is expected to find its own market for electricity. If that is the case, private companies will explore power trading opportunities in India,” he said. “The government should not be directly involved in hydropower development—it should focus on generating revenue through royalties from private sector projects.”

NEA’s dual role as both a regulator and a market participant creates conflicts of interest and discourages competition. NEA sets electricity tariffs, manages transmission infrastructure, and generates power, allowing it to control market conditions and favor its own projects over private sector initiatives. This centralization of power, developers say, leads to delays in project approvals, restricted access to transmission infrastructure and an uneven playing field for them.

Those advocating for the NEA unbundling argue that the main goal of unbundling is to create clear distinct roles for each entity. According to them, power generation would be handled by private developers and independent producers, while transmission and distribution would be managed separately by public or private operators. Policy-making and regulation would remain under government control, ensuring fairness and transparency.

This structure would allow the electricity market to function more efficiently, with private developers focusing solely on production, while transmission and distribution companies work to improve infrastructure. The urgency for unbundling has grown due to Nepal’s increasing power export potential. Currently, Nepal relies heavily on India and Bangladesh for power exports, but NEA’s monopoly over electricity trading makes the process inefficient and bureaucratic. By separating generation and transmission, Nepal could streamline power trading and improve its negotiation capabilities with international buyers.

According to Karki, IPPAN has already signed Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with Indian energy companies for power trading. "As a result, 4-5 companies have been registered in Nepal for power trading. But they have not yet received the necessary licenses. If the private sector had the appropriate trade licenses, they would be able to trade energy more freely and efficiently," he added.

Fate of Projects After 35 Years

A bill to make an amendment to the Electricity Act is pending in parliament. A key provision in the proposed law seeks to claim ownership of hydropower projects after 35 years-significant shift from the Electricity Act, 1992, which grants a 50-year license period of hydropower companies.

This change has sparked concerns among private power developers, particularly those who finance projects through public IPOs. Under the current law, after 50 years, a project can be relicensed to the same company. However, the proposed reduction in license tenure creates uncertainty, especially for long-term investors.

IPPAN President Karki warns that such a policy shift could undermine investor confidence and discourage private sector participation. "If individuals invest in a project for 25 years, can the government simply take away their shares without fair compensation?” he questioned. “By the time Nepal reaches its 28,500 MW hydropower target, most investment will come from Nepali citizens. Any change in policy must be carefully evaluated to protect investor trust."

Nepal currently follows the BOOT (Build-Own-Operate-Transfer) model in hydropower development, with domestic hydropower projects receiving 35-year licenses and foreign-invested projects receiving 30-year licenses, with extensions permitted up to 50 years.

However, misconceptions about project viability after 30-35 years have led to unnecessary confusion, according to Pokharel of Urja Developers.

The proposed law also extends the BOOT model to transmission and distribution infrastructure, requiring private developers to transfer ownership to the government at the end of the license period without compensation.

According to IPPAN, mere state ownership does not guarantee optimum asset utilization. Instead, removing the BOOT requirement for transmission and distribution could encourage long-term private sector engagement in the energy sector. IPPs suggest that allowing private developers indefinite operation of transmission and distribution infrastructure could ensure continued private-sector efficiency and innovation in the sector.

***

Large projects entail both risks, rewards

As someone involved in the sector since 2005, I have witnessed Nepal’s progress in hydropower development firsthand. While it took Nepal 107 years—from the 500 KW Pharping plant in 1911 to reaching 1,000 MW of installed capacity by 2018, the subsequent seven years saw addition of an impressive 2,200 MW, primarily driven by private sector investment. Globally, private capital has been a key driver of development, and in Nepal, private investment has played a significant role in expanding hydropower. While the private sector invests through equity, public institutions such as banks make debt financing and the general public contribute through IPOs.

Under the BOOT model, hydropower licenses of 35 years are granted for projects with domestic investment and 30 years for projects with foreign investment. However, the law permits licenses to be issued for up to 50 years. The misconception that projects become non-viable after 30-35 years is creating unnecessary confusion. Project development follows key stages like pre-feasibility study, feasibility study, detailed project report (DPR), technical refinement and implementation. Typically, consultants are engaged for these phases. However, in Nepal, there is no legal framework holding consultants accountable, leading to misalignment between planning and execution. This results in cost overruns, delays, and quality concerns.

Recognizing these structural gaps, we established Urja Developers in 2016. Our ecosystem includes an engineering company responsible for design, implementation and project management from inception to completion. Once construction is complete, operation and maintenance become critical concerns. To address long-term technical sustainability, we created Urja Services. Additionally, sustainability across technical, financial, environmental and resilience aspects is vital. To uphold Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) standards, a dedicated body within Urja oversees these areas.

Urja has already completed two projects, one of which received international recognition—a gold certification from the International Hydropower Sustainability Alliance. Currently, we are operating two projects and have four under construction. Among them is the 73.5 MW Middle Mewa project, Nepal’s first private-sector peaking plant with a six-hour storage capacity. Other projects include a 9.3 MW plant in Taplejung, two projects in Myagdi with capacities of 53.5 MW project and 64 MW. All are expected to be completed within four years. Looking ahead, we are planning a major initiative—the 420 MW Urja Tila Power Project.

Executing large-scale projects in Nepal is, however, difficult due to limitations in engineering and construction capacity. In terms of debt financing, liquidity crises in the banking system have created difficulties in the past. To ensure financial stability, a blend of debt financing, equity and foreign investment is necessary. In collaboration with IFC, we introduced mezzanine financing in Nepal, structured as an NPR-denominated instrument worth $21 million. However, as mezzanine financing is a new concept in Nepal, approval delays from Nepal Rastra Bank have hindered its implementation.

Large projects entail both risks and rewards. If executed properly, they benefit from economies of scale. In other countries, the private sector operates with a degree of certainty, but in Nepal, policy inconsistencies, legal hurdles, resource constraints, price hikes due to cartelization and bureaucratic delays create major challenges.

Over the past 25 years, Nepal’s hydropower financing has evolved significantly. Earlier, a consortium of 8–10 banks would collectively finance a 3 MW project, whereas today, a single bank finances up to Rs 9 billion, with co-lead banks financing Rs 7 billion for a single project. The government must do more to facilitate private sector participation. While policies such as mandatory hydropower financing by banks have been introduced, it alone is not sufficient.

The biggest challenge is the market. Our domestic consumption is not even 2,000 MW. Currently, only 4% of Nepal’s total energy consumption comes from electricity. Nepal must increase electricity’s share of total energy consumption from 4% to at least 30-40%.

At present, Nepal’s power generation is heavily dependent on the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA). However, major risks must be addressed: What if NEA is unable to sell surplus power in the future? What if India ceases to purchase excess electricity due to geopolitical issues? What if NEA’s financial health deteriorates? Such uncertainties underscore the need for private sector participation in power trading.

Enabling private sector involvement in power trading is crucial for Nepal’s energy security. Private sector participation will enhance energy trade and stability. By 2030, Urja Developers aims to build a portfolio of 1 GW. We are confident in achieving this target and are actively seeking new projects, including the integration of solar power into Nepal’s energy mix.

***

Govt must create enabling environment

For years, we have heard that hydropower will transform Nepal. The foundation for private sector participation was laid in 1992 with the introduction of the Electricity Act. Initially, small-scale projects were developed. By 2000-01., private sector involvement had increased, but confidence among banks and investors remained low due to uncertainty over electricity demand.

From the mid 2000s, private sector investment gained momentum, and by the mid-2010s, the industry experienced rapid growth. Over the last decade, the private sector has developed 70% of Nepal’s total hydropower capacity.

Nepal currently generates 3,500 MW of electricity, with private developers contributing 2,740 MW, showcasing the sector’s significant contribution. Projects with a combined capacity of 4,500 MW are under construction and expected to be completed within the next two or three years. An additional 3,000 MW worth of projects are in the financial closure stage, while projects totaling 10,000 MW are in the pipeline.

With the right government support and policies, Nepal can achieve remarkable success in hydropower. Private developers are now handling projects ranging from 100 MW to 300 MW, and investor confidence is at an all-time high. Banks, which were once hesitant, are now investing Rs 7–8 billion in single projects.

The government’s agreement with India to export 464 MW has further reassured private investors that electricity production will not go to waste. Nepal’s progress—from 1 MW projects to 35 MW, then 110 MW, and now 220 MW—demonstrates the potential for rapid expansion. However, policy reforms are essential to sustaining this growth.

One major obstacle is bureaucratic red tape. Currently, hydropower developers must secure approvals from multiple offices instead of following a streamlined process under the energy ministry. Simplifying these procedures would significantly accelerate project development.

Nepal’s private sector must also be allowed to sell surplus electricity in international markets. If included in cross-border electricity trade agreements, Nepali companies could actively participate in regional power markets. However, the biggest challenge remains Nepal’s weak transmission infrastructure, which requires urgent upgrades.

At present, 290 private sector projects are under development. Previously, 100 projects generated 2,000 MW, but with advanced technology and efficiency, 100 new projects could now generate 10,000 MW. However, many 100 MW projects are stalled due to delays in securing Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs).

Despite increased production, Nepal still relies on electricity imports from India during the dry season. To achieve energy security, Nepal must expand its industrial sector while ensuring a consistent, 24/7 electricity supply to industries and phasing out diesel use.

Private sector investment in hydropower is governed by the Electricity Act, 1992, which grants 50-year licenses. According to this law, projects can be handed back to the same company after 50 years. However, proposed government changes to the licensing system have raised concerns among investors, particularly given the large public investment in hydropower through IPOs. If individuals invest in a project for 25 years, can the government take their shares without fair compensation? By the time Nepal reaches 28,500 MW production, most investments will come from Nepali citizens, making it crucial to review policies carefully to maintain investor confidence.

The rising cost of hydropower projects is another pressing issue, driven by price manipulation in construction materials. Cement prices increased by Rs 200 per bag due to cartelization, and iron bar prices have also surged, inflating overall project costs.

Hydropower has the potential to transform Nepal, but this requires policy consistency, streamlined approvals and infrastructure development. The private sector has proven its capabilities, but the government must create an enabling environment by addressing transmission constraints, supporting energy exports and ensuring fair policies for long-term investors.

If Nepal fully harnesses its hydropower potential, it can not only meet domestic demand but also become a major electricity exporter—driving economic growth and industrialization.

***

Overall energy demand not growing due to low industrial consumption

The first privately developed project was the 3 MW Piluwa Khola project in Sankhuwasabha, financed by a consortium of eight banks. Over the years, the banking sector's capacity has expanded significantly.

Through Arun Valley Hydropower Development Company, we have successfully developed the 3 MW Piluwa Khola and the 10 MW Kabeli Cascade projects. Additionally, Arun Kabeli Power Limited has developed Kabeli B1 (25 MW) and Kabeli A (35 MW), with Butwal Power Company also involved in the latter. Kabeli A is expected to be connected to the national grid within the next 6–8 months. We have also partnered with Ridi Power Company to build a 2.4 MW project and collaborated on an 8 MW solar plant in Butwal. The 9.7 MW Ingwa Khola project has already been integrated into the national grid.

Api Power Company has focused on hydropower development in Sudurpashchim Province. We successfully completed the 8.5 MW Naugad Gad Small Hydropower Project and the 8 MW Upper Naugad Gad Project, both have now been connected to the grid. In Darchula, the 40 MW Upper Chameliya Project is also operational.

Meanwhile, Ingwa Hydropower Company has developed the 9.7 MW Ingwa Khola project. The Upper Ingwa Khola project is also complete, while the Lower Ingwa Khola project is under construction. PK Hydro is developing a 30 MW project on the Likhu River, and Sajha Power Company is constructing the 25 MW Lower Balephi Hydropower Project.

Beyond hydropower, Api Power Company is expanding into mixed energy sources with solar projects. Our business model operates multiple companies under one umbrella, with a primary focus now on high-voltage transmission line development. Api Power has invested a total of Rs 50 billion across its various projects. However, equity management remains a major challenge in large-scale projects. Currently, hydropower developers must navigate through 12 ministries and 24 departments just to secure licenses. This cumbersome process needs to be reformed by introduction of a single-door policy.

The government has set an ambitious goal of producing 28,500 MW of electricity. However, without improvements in transmission infrastructure, this goal will face significant bottlenecks. Even if domestic electricity demand increases by 1,000 MW, there is currently no adequate infrastructure to support it. Industrial consumption remains low due to economic downturns, and overall electricity demand is not growing as expected. Furthermore, political instability and geopolitical challenges pose significant risks. If Nepal is unable to export surplus electricity to India or other countries, it could threaten the long-term sustainability of hydropower investments.

Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) should be unbundled. No other country allows a single institution to handle policy-making, electricity trading, transmission line development and project implementation simultaneously. Currently, the private sector is expected to find its own market for electricity. If this continues, private companies will explore power trading opportunities in India. We believe that the government should not be directly involved in hydropower development but should instead generate revenue through royalties from private sector projects.

There is also significant confusion about what happens after 30–35 years under the BOOT model. Additionally, the current provision related to promoter shares is also problematic. In the banking and financial sector, shares are categorized into public and promoter shares. The hydropower sector should adopt a similar model, ensuring that promoter shares remain distinct and are not locked indefinitely. Once the lock-in period ends, promoters should have the option to sell their shares. Investors need a clear exit strategy to confidently invest in projects. A provision should be introduced allowing promoters to offload 60–70% of their shares but only after project debts are cleared.

The Securities Board of Nepal (SEBON) should implement a “fit and proper” test for hydropower promoters. Strict guidelines must be enforced to ensure promoters are not blacklisted, have clean sources of capital, possess corporate governance knowledge and have no political affiliations. A net worth evaluation should also be conducted. Additionally, capital raised through IPOs must be monitored to ensure proper utilization. Cost overruns and project delays should be strictly regulated, with penalties imposed for mismanagement.

***

Bureaucratic hurdles a major deterrent for investors

Tamor Energy’s journey began with the 1 MW Pathi Khola Small Hydropower Project in Parbat. However, this venture faced various challenges, particularly with road construction and transmission lines. High cement prices also added to the financial burden.

Following the completion of the Pathi Khola Project, Tamor Energy successfully developed the Sikles Hydropower Project and the 15 MW Hewa Khola Project. However, securing financing remained a major challenge. For Hewa Khola, we needed Rs 1.8 billion in loans which was fulfilled by a consortium of 11 banks. Since banks had limited capital at that time, each bank committed Rs 250 million—a substantial undertaking at that time. The project ultimately cost Rs 170.54 million per MW because of policy inconsistencies, such as a delayed tax exemption on spare parts, drop up expenses. Although the government promised a tax exemption worth Rs 100 million on spare parts, customs authorities held up these parts for eight months, causing delays and additional costs of Rs 1 billion. Such policy inconsistencies continue to deter investment in new hydropower projects.

Currently, Tamor Energy has successfully connected 300 MW of hydropower to the national grid, with an additional 250 MW expected to come online in the next two years. One of the company’s major ongoing projects is the 285 MW Upper Tamor, which will be the first private-sector project in Nepal to use a tunnel boring machine (TBM). The project costing Rs 51 billion is yet to reach financial closure.

Other ongoing projects include the Super Madi (44 MW), the Riverside Hydropower (47 MW) and the Palung Khola (21 MW). Altogether, these six projects represent a total investment of Rs 85 billion and are to generate Rs 17 billion in annual revenue upon completion. This revenue will support reinvestment in future projects, enabling the company to mobilize Rs 100–200 billion over the next decade.

Tamor Energy is also committed to corporate social responsibility (CSR), particularly in the Upper Tamor region. The company has invested Rs 320 million in the area–more than the entire budget of Phaktanglung Rural Municipality. Once operational, the Upper Tamor project will provide the municipality with Rs 70 million annually in royalties. Additionally, Rs 5 billion will be contributed to the government as tax revenue during the project’s construction phase.

Nepal’s private sector are developing large-scale hydropower projects, dispelling the notion that Nepali investors cannot handle 100 MW projects. Stronger equity management and the government’s mandate requiring banks to invest at least 10% of their portfolios in hydropower have bolstered investor confidence.

However, concerns persist over Nepal’s electricity exports to India. The country currently imports 700 MW from India, costing Rs 22–25 billion annually. Achieving energy independence will require a reliable electricity supply during the dry season, including maintaining a 20% energy reserve to offset seasonal shortfalls.

Nepal’s hydropower sector also faces challenges related to energy spillage during the wet season, with around 33% of annual revenue lost due to excess energy production during the four-month period. If Nepal stops importing electricity, surplus energy could be directed toward value-added industries, such as high-grade iron or silicon production, both of which require substantial power. Data centers also present a promising investment opportunity due to their high electricity demand.

Despite these opportunities, bureaucratic hurdles remain a significant obstacle. The complex and time-consuming process of obtaining explosives for hydropower construction is just one example of regulatory challenges that slow infrastructure development. Simplifying these procedures is crucial to accelerating hydropower growth

***

Nepal to benefit from global demand for power

The Piluwa Khola 3 MW Project was carried out by a dedicated team of 6-7 individuals, including Hari Bairagi Dahal, Guru Prasad Neupane, Hari Pandey, Dedh Raj Khadka, Anup Acharya and myself. The initial financial closure required collaboration with multiple banks. Over time, the capacity of our projects grew from 1-2 MW to 5-10 MW, eventually reaching 50 MW, with plans to scale up to 100 MW.

The core team members, who worked on this project, have since established their own independent companies. They continue to thrive and make significant contributions to Nepal’s hydropower sector. Currently, we are constructing a 216 MW project, and our group is prepared to develop up to 500 MW in total. This marks a major milestone for private-sector hydropower development in Nepal and presents a significant opportunity for the country

In my opinion, three factors have shaped Nepal’s hydropower ecosystem. The late Energy Minister Sailaja Acharya took the initiative to establish the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) rate, incentivizing new investments in the sector. Former NRB Governor Chiranjivi Nepal, played a pivotal role in expanding banking capital during his tenure, increasing it to Rs 8 billion. This enhanced the lending capacity of banks and enabled the financing of 30-40 MW projects. The private sector has been instrumental in driving policy reforms and expanding Nepal's hydropower capacity. For sustainable growth, banks must increase their lending capacity. Each bank should have a minimum capital base of Rs 25 billion to ensure smooth financing for large-scale projects. Additionally, projects with 100% Nepali investment should be granted 50-year licenses to encourage long-term domestic participation in the sector.

Nepal is well-positioned to benefit from the global demand for power. Once connected to India and Bangladesh, Nepal can export power on a large scale, particularly to energy-deficient regions like Bihar state of India. To facilitate project development, Nepal needs a single-window approval system. Countries like Russia, Thailand and Singapore have successfully implemented single-window approval systems to streamline project development. Nepal should adopt a similar approach to reduce bureaucratic hurdles and accelerate implementation of projects.

Many projects are struggling to achieve financial closure due to reliance on collateral-based financing rather than project-based financing. The central bank mandates that banks allocate a position of their investments to agriculture, tourism and hydropower, but this policy needs to be revised. Banks should be required to invest at least 20% of their portfolios in hydropower, ensuring adequate capital flow into the sector. Moreover, the cap on individual bank lending is another constraint. Currently, a bank can only provide 25% of a project’s total capital, with a maximum lending limit of 50%. This restricts the ability of banks to support large-scale projects effectively

In areas like Rasuwa, where electricity can be provided at Rs 5 per unit, an intermediary like the NEA is necessary. Allowing direct supply to industries would lower costs and support industrialization, making power more affordable for businesses. Our team is currently operating 100 MW projects, with projects having combined capacity of 300 MW under construction. Our largest ongoing project is the 216 MW Upper Bajhang Seti project in Sudur Paschim which is estimated to cost Rs 200 million per MW.

To complete these projects, we must obtain 22-25 approvals from government agencies. Streamlining this process would significantly accelerate Nepal’s hydropower development.

(This news report was originally published in April 2025 issue of New Business Age Magazine.)

you need to login before leave a comment

Write a Comment

Comments

No comments yet.