Cement manufacturers in Nepal are intensifying their campaign to promote concrete roads, citing their durability, lower long-term maintenance costs, and resistance to erosion and water damage. Unlike traditional blacktopped roads, concrete pavements are being increasingly viewed as a sustainable alternative for Nepal’s challenging terrain and climate.

Concrete paving is currently underway along segments of the 197-kilometre Sandhikharka–Dhorpatan road, particularly in sections vulnerable to wear and tear. According to Gagal Bahadur Bhandari, Chief of the Sandhikharka-Dhorpatan Road Project, concrete is being used selectively along roughly two kilometres of a 48-kilometre stretch. The focus is on steep inclines, turning points, and areas with minimal sunlight, where bitumen roads typically deteriorate quickly.

While constructing one kilometre of concrete road costs between Rs 30 million and Rs 35 million—about three times more than the Rs 10 million required for surface dressing—experts argue that the longevity of concrete justifies the initial investment. Concrete roads can last up to 40 to 50 years and require significantly less maintenance over time.

Other regions are also seeing similar efforts. In the Kathmandu Valley, concrete has been used in sections of the Tinpipley–Suryabinayak–Dhulikhel road and in high-traffic areas like bus parks. However, not all attempts have been successful; for instance, the concrete road in the Bahrabise–Tatopani section suffered damage during heavy rains. Still, engineers maintain that concrete is ideal for erosion-prone or waterlogged areas.

Dr. Sunilkumar Saxena, Chair of the Cement and Concrete Committee at the Bureau of Indian Standards, highlighted India’s growing use of concrete roads during a presentation in Nepal. He cited the Delhi–Mumbai Expressway, where concrete pavement has reduced travel time and enhanced road durability. Similar projects are underway in states like Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh, where concrete is also being used in smart cities, industrial corridors, and rural roads. According to Dr. Saxena, while concrete roads cost more to build (Rs 120 million to Rs 150 million per kilometre in India compared to Rs 80 million to Rs 100 million for asphalt roads), they offer substantial savings in fuel consumption and long-term upkeep.

Rajendra Raj Sharma, Undersecretary at Nepal’s Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport and a concrete road expert, acknowledged both the advantages and drawbacks. He noted that while concrete roads are environmentally friendly, safe, and durable, they pose challenges in urban areas where underground utility installation is frequent. Once built, concrete roads are harder to break for maintenance or upgrades. Sharma also pointed out that Nepal’s first concrete road was built in 1950 along Tridevi Marg in Thamel.

Nepal’s cement manufacturers are backing the move toward concrete roads as part of a broader strategy to address declining domestic demand. Following a post-earthquake construction boom in 2015, cement consumption has slowed, leaving manufacturers with excess capacity. Nepal currently has 65 cement factories with a total investment of Rs 300 billion and an annual production capacity of 25 million tonnes, while domestic demand is only about 10 million tonnes. The industry directly or indirectly employs more than 100,000 people.

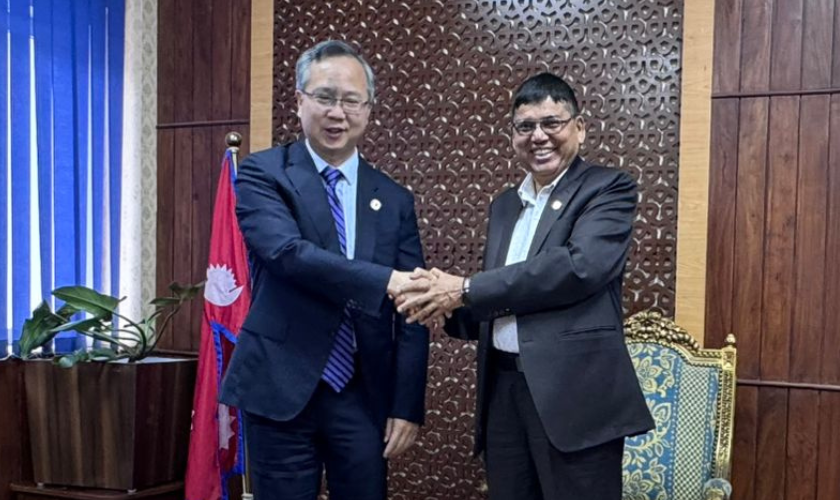

To promote concrete roads as a market for surplus production, the Nepal Cement Manufacturers' Association has been lobbying the government since 2021. On Monday, it hosted a "Cement-Based Road Conference" with the slogan "Not Blacktop, Let’s Go White." The event brought together Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Urban Development Prakash Man Singh, Minister for Physical Infrastructure and Transport Devendra Dahal, and Minister for Industry, Commerce and Supplies Damodar Bhandari, along with other government officials and engineers.

Speaking at the event, Minister Dahal emphasized the need to expand concrete road projects as a means to boost domestic cement use. He cited a four-kilometre concrete road in Daunne being extended to six kilometres under a pilot project. Similar feasibility studies are ongoing in other regions. However, Dahal cautioned that not all roads can or should be built using concrete and called for a public-private partnership (PPP) model to assess where the approach is viable.

Association President Raghunandan Maru urged the government to establish clear legal and policy guidelines for concrete road construction. He highlighted the Nagdhunga–Naubise section, which is under consideration for concrete paving, as a model for replication in other suitable areas.